Director of philanthropic advisory services at BMO outlines how this vehicle can serve the kind of strategic giving that HNW clients want

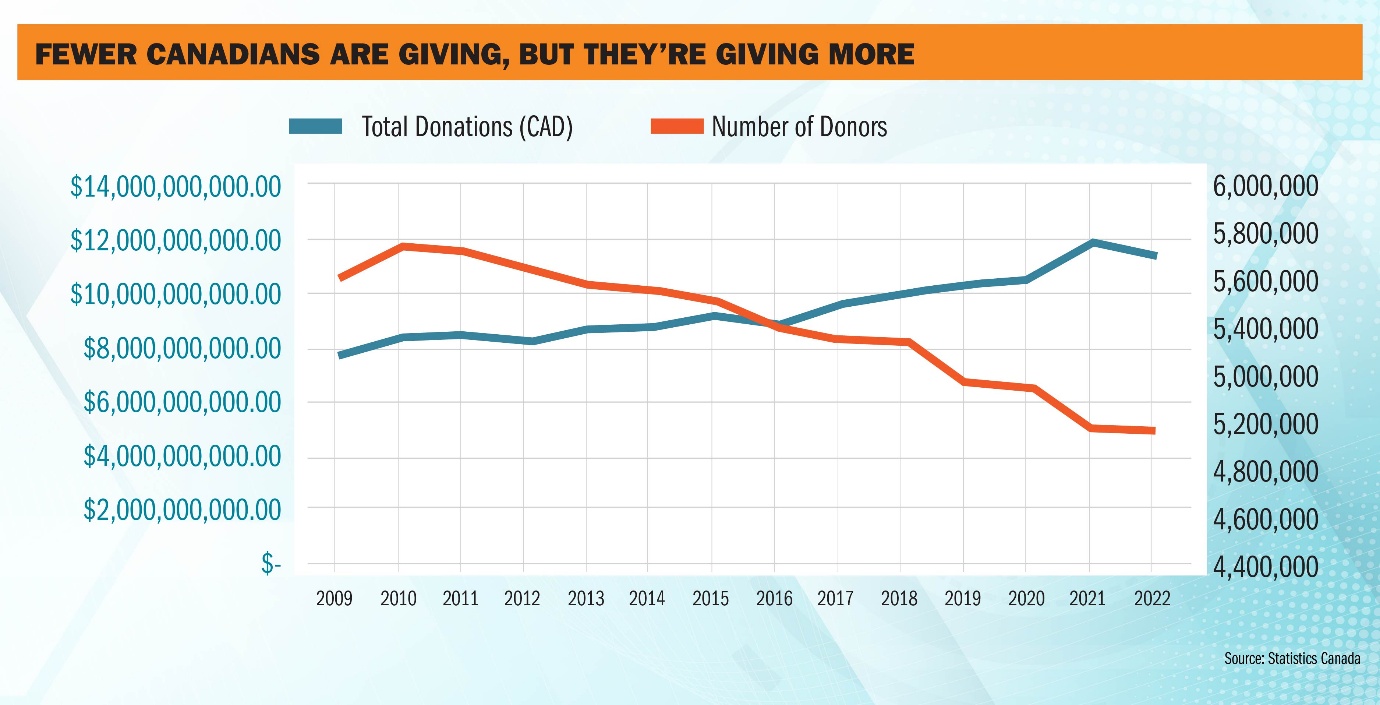

Fewer Canadians are giving to charities, but those few are giving far more. Statistics Canada data has shown that between 2009 and 2022 more than six hundred thousand fewer Canadians have filed a donation claim on their taxes — a roughly 12 per cent drop, not accounting for population growth. At the same time, the total number of donations have increased from $7,750,405,000 to $11,432,695,000, an increase of almost 48 per cent. Larger gifts from fewer donors reflects the rise of philanthropy among high net worth (HNW) Canadians, and a prospective opportunity for advisors seeking to serve these investors.

As advisors look to build out their philanthropic services to serve and retain HNW clients, they may want to consider the utility of donor advised funds (DAFs). That’s the view espoused by Karen Sparks, director of philanthropic advisory services at BMO. She explained that these funds can weave philanthropic giving into a holistic financial plan, while utilizing the tax benefits inherent in the charitable donation of securities. She outlined, as well, some of the limits of these funds and the decisions advisors and their clients will need to make regarding their use. At a time of the year when many Canadians think about their charitable gifts, Sparks sees a moment where a conversation about DAFs can help advisors set themselves apart.

“The whole idea is to set up a separate fund that will grow over time, and yes, you get the tax receipt for any gift that's made to the fund. But there's also the ability to amplify your giving over time by creating a tax-exempt fund that is 100% devoted to charitable purposes. And as we like to say in the industry, give it, grow it, grant it,” Sparks says. “Donor advised funds offer the ability to give more to charity overall, which really appeals to donors who want to take their giving to the next level. Instead of providing a credit card, you are able to be a bit more thoughtful and impacting with your giving because it is planned out.”

It's that intersection of financial planning and philanthropic giving which Sparks believes makes DAFs such a powerful tool for advisors. She adds that these funds typically have a relatively low minimum asset requirement, though that will vary based on the institution these are set up through.

Advisors, Sparks says, will be able to find key moments to raise the prospect of DAFs as they watch their clients’ giving habits. When clients typically give cash or securities, advisors can talk about setting up a philanthropic structure like a DAF that aligns with client goals. Philanthropy can also arise in a standard values conversation as the advisor learns more about their client.

The DAF conversation can also come about during a significant liquidity event, like when an entrepreneur client sells their business. Sparks notes that these events can often generate a huge tax bill, and philanthropic giving may be a significant part of how the client plans to offset some of that bill while growing their giving impact. The trouble is, a moment like selling a business is often extremely busy and quite emotionally charged. Deciding exactly where to donate at that time can be challenging. Setting up a DAF, Sparks says, can mean the client triggers their tax receipt now while deferring the final donation decision.

While the client retains input in the use of their gifted funds, giving advice to their charity of choice, Sparks emphasizes that the charity has final decision over the use of the gift. Moreover, it’s important for clients and their prospective heirs to understand that once the money is gifted in a DAF, they can’t get it back. Sparks says that advisors and clients setting up a DAF need to discuss what happens to the fund after the clients pass away, whether legacy instructions will be left with the foundation or if a family member will be named the successor advisor to the fund.

Recipients, too, need to bel listed as a qualified donee by the CRA. That list includes every registered charity in Canada, as well as many Canadian and international universities and international organizations like UNICEF. Given that many Charities may not have brokerage accounts, using a DAF can give additional flexibility to the strategy of donating securities, which can have significant tax benefits for clients and upside potential for charitable recipients.

There is also the potential benefit of using DAFs to guide the intergenerational wealth transfer. Sparks notes that key in this process is the education of that inheritor generation about wealth stewardship. Philanthropy can be a tool to help with that education. It can also help with the overwhelmingly female population of Canadian inheritors. Sparks notes that women have tended to prefer a more planful approach to philanthropy, and DAFs are a tool that aligns with that approach.

For advisors seeking to serve a wealthier and typically older client base, Sparks says the importance of philanthropy can’t be overstated. She believes that DAFs can play a key role in advisors’ service of these clients’ philanthropic goals.

“According to StatsCan data, the older you get, the more likely you are to make a charitable gift. This is part of this intergenerational wealth transfer that's taking place,” Sparks says. “As a financial planner, it's as people get more comfortable and are less worried about running out of money, then they tend to be a little bit more willing to give some of it away.”