Industry experts outline common challenges, points of dissonance, and best practices for exiting advisors

For independent advisors, the ability to sell their business to a successor represents the culmination of a long and fruitful career in the financial services industry. But according to one expert, the majority who go through the process look back on it as a bittersweet experience.

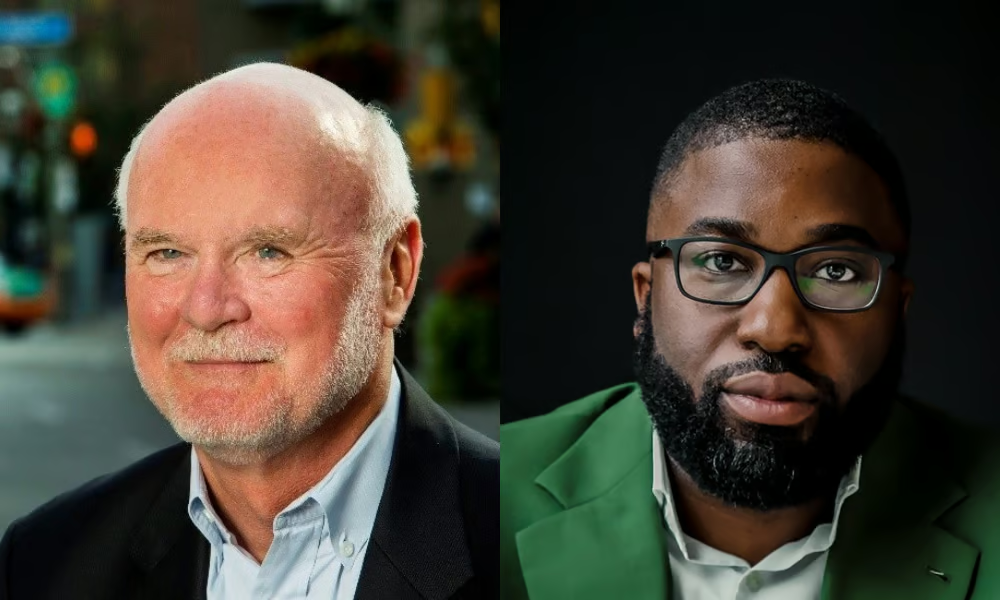

“Three out of four advisors who’ve retired express some remorse or regret over how they left the business,” says George Hartman, founder of the advisor consulting firm Ultimate Practice (pictured above, left). “Those can span all the way from ‘I didn't leave my clients in proper hands’ to ‘I didn't help with the transition,’ or ‘I didn't sell my practice for enough money’ … ‘I sold too soon’ … ‘I waited too long.’”

Multiple hurdles to a graceful succession

According to Hartman, succession can be challenging to advisors from a financial perspective; he’s surprised by the number of advisors who don’t realize the lifestyle implications of moving from a high-cashflow business to living on a lump sum from the sale of their successful practice.

George Boahene, another succession planning expert, says advisors often navigate the technical issues first: ensuring their business transition is tax-efficient for them, and making sure their successor understands their business and industry.

“What makes succession such a money- and time-exhaustive process is the emotional or the soft side of it,” Boahene (above, right) says. “Advisors have such a high emotional attachment to their business – some of them call it ‘my baby’ – and to their clients. It’s not so easy for many advisors to let go.”

“You've spent 25, 30, 35 years building a great business … you’ve poured your heart and soul into it,” Hartman says. “There are ego issues and relevance issues: How am I going to spend my time? Will people still respect me? Will they still think I’m a good guy or gal?”

According to Boahene, valuation is another challenging aspect for many exiting advisors: the complexities of valuating their business aside, many struggle to assess the support and resources required in their next phase of life. There’s also the fact that advisor often leave it to the 11th hour to do their succession planning.

“You didn't grow your business overnight. So how would you transition out of the business in the same manner?” he says.

“Choosing the right successor is particularly complicated,” adds Hartman. “There are lots of people out there who want to buy your book of business, but they're not necessarily the ones you want as a successor.”

Boahene is seeing a dissonance between today’s retiring advisors, many of whom built their businesses by going door-to-door, and today’s younger advisors who are putting in a different kind of sweat equity. Finding advisors with sufficient skills and competencies to take over, he adds, has become a major point of conversation.

“Everyone aspires to hand their business off to somebody who’s either more credentialled or holds sufficient tenure,” Boahene says. “Realistically, you’d want someone who’s either at the same or at a higher level of proficiency and has a high degree of fit with clients.”

The long and winding road

At Hartman’s advisor consulting business, he starts succession-planning engagements by asking clients to answer two big questions: “Am I ready to exit my business?” and “Is my business ready for me to exit?”

“The second question … is all about leaving your clients in the best possible hands,” he says. “Quite frankly, I’m thrilled at how often advisors tell me their biggest concern is for their clients – many of whom have become friends over 25 or 30 years – to be well looked after when they leave. So you know it’s not all about the money.”

From a timing standpoint, both Boahene and Hartman agree it’s important to create as long a succession-planning runway as possible. Compared to the 12- to 18-month timeframes that advisors would contemplate when he first started coaching around succession planning, Hartman says three to five years is very common nowadays, and five- to 10-year schedules are quite common.

“Understand that your business is dynamic. Your business changes, and so should your plan,” Boahene adds. “Often, I say succession plans are built with good intentions, documented by professionals, and then put in a drawer to die. … You pull it out at the last minute, and you realize that this does not reflect the growth in my business or where my business is today. So it should be reviewed on an annual basis.”

While advisors who do succession planning for their clients may be tempted to handle their own, Boahene says exiting advisors and planners should not be afraid to seek professional help as well.

“It's always easier for someone who has an objective opinion, to stand back and see something you don't,” he says. “They're not in the weeds … they can stand back from the emotional turbulence you will experience.”