Unpacking the barriers to retirement for Canadians that advisors need to be aware of now

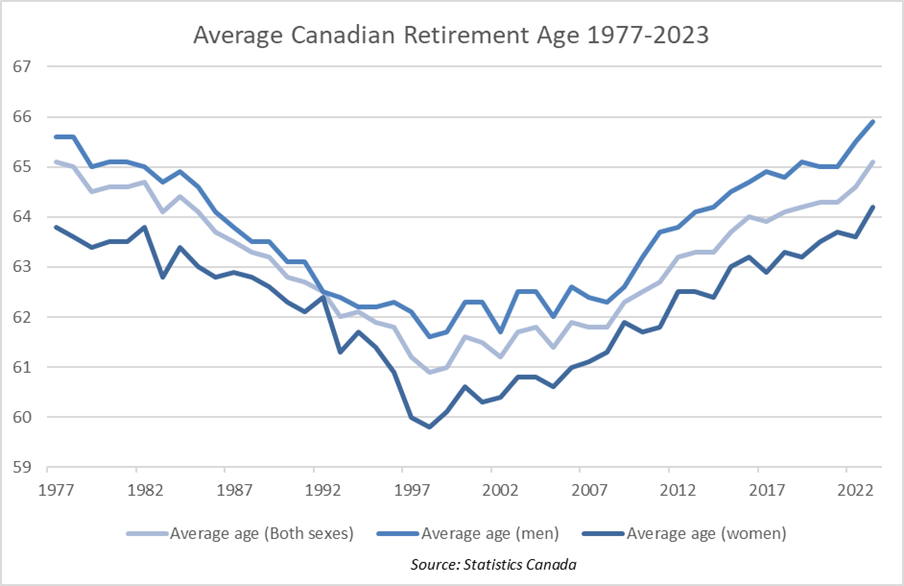

Between 1977 and 1998 the average retirement age in Canada for all employees fell from 65.1 to 60.9, according to Statistics Canada. Between 1998 and 2023 it has risen back to 65.1. Those three numbers and the U-shaped trendline they draw, tell a story that Tanya Staples believes Canadian advisors need to be aware of.

Staples is a Professor of Financial Planning at Conestoga College, she holds a CFP® designation and is currently a PhD Candidate at Kansas State University’s in the Personal Financial Planning Program. She is also still a practicing financial planner. Citing academic research and personal experience she highlighted the myriad trends that have underpinned this 27-year rise in Canadians’ retirement age and what it means for Canadian financial advisors working to help their clients achieve that retirement goal. While financial security is key to Canadian retirement, Staples emphasizes that there are a few key personal factors that can play a deciding role.

“If we look at some of what registered psychologists have talked about, Canadians need to retire to something,” Staples says. “That’s particularly the case for men. As employees, we get a lot of our value, our self-worth, and our sense of how we contribute to the world from our jobs. Statistically, women are more likely to have a larger social network outside of the workplace. It’s often easier for women to transition into post work because they already have that network established whereas men will struggle more. So, we have to look at what their identity will be in retirement. I think that's where financial advisors can really add value, by beginning that conversation around retirement identity.”

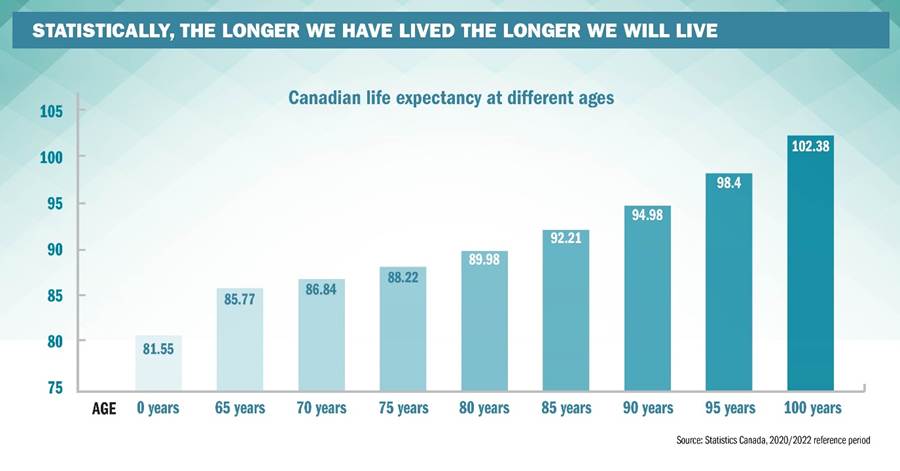

Of course, financial foundations are key to establishing that retirement identity. In that area, too, Staples notes the challenges that many Canadians face. She cites research conducted by G Schellenberg and Y Ostrovsky in the leadup to the GFC which noted the importance of access to a pension plan — ideally a defined benefit pension plan — in helping people feel secure enough to retire. Over the past three decades, Staples says, we have seen declining pension access in Canada. That lack of access, she says, is a key reason why fewer Canadians are retiring early. At the same time, Canadians are living longer, meaning they have to save and budget for a longer retirement, often without the support of an employer-sponsored pension plan.

Many Canadians are entering pre-retirement with considerable amounts of debt, too. Many are also aging with the expectation that their CPP and OAS benefits will function as their pension income — rather than just a backstop against dire poverty. Staples says that the income cohort between roughly the average industrial wage and around $120,000 is where financial advisors can make a significant impact. That cohort, she says, lacks meaningful retirement savings, while carrying the highest percentage of debt relative to income and assets. This leaves them vulnerable to experience retirement income insufficiency without an employer pension. They may not be aware of their situation, either, as some expect government pensions to provide them with enough. They very likely have some serious challenges to overcome before they can securely retire, and advisors can help them a great deal.

The trouble, for advisors and advisory firms, is that this income cohort is not exactly profitable. Commission-based advisory services are less incentivized to help with the financial plans these Canadians need. Fee based advisors, at the same time, are incentivized to chase larger account sizes. In seeking solutions Staples says she has encountered pro-bono programs offered in the United States. While Canada is behind our US counterparts somewhat, Staples notes a few efforts such as the push by FP Canada to increase access to financial planning. The Financial Planning Association of Canada (FPAC) also has a pro-bono committee where members regularly volunteer their time to help build plans for Canadians

There may also be a degree of future planning involved in taking on some nominally lower income clients. Much of Staples’ research looks through the lens of gender at the situation facing retirees. Among the many surprising trends she’s unearthed she notes that according to StatsCan, in 2022 more women became covered by pension plans than men. This reversal, she notes, is the product of a number of factors including the increasing role of women in the workforce, the overall rollback in pension access, and the disproportionate presence of women in professions still able to access pensions like teaching, nursing, and the public service.

As advisors look at these women, who are statistically more likely to live longer, who tend to have lower risk tolerances, and who have often taken time out of the workforce, Staples highlights another key trend: women are set to inherit a vast amount of wealth. Women’s wealth in Canada is set to rise from $2 trillion to $4 trillion by 2028, largely as a result of the intergenerational wealth transfer. Canadian women are staring down the business end of a worsening retirement crisis, but they may also represent a massive area of opportunity for the advisors whose services they sorely need.

“There’s a perfect storm of reasons to support these women, but there are so few female financial planners in Canada and the US. Research suggests that women want to be serviced by financial planners who are women, or who at least understand what they value as a woman,” Staples says. “So, I think there’s an incredible opportunity for firms and advisors to support women who want to be CFP professionals and who want to support female clients in their retirement plans.”